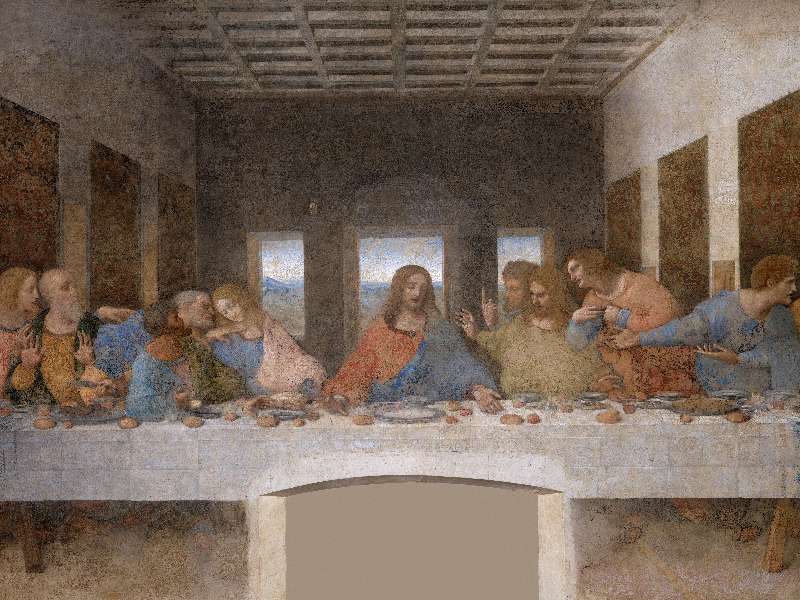

Last Supper

Excursions

Shopping Experience

Secret Milan

A Night at the Duomo

A Night at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

이벤트

이미지 갤러리

이벤트 정보

An Emperor's Jewel

불가리 소개